Experts say kids are more stressed today than ever before. That’s no surprise.

Experts say kids are more stressed today than ever before. That’s no surprise.

We see the fast-paced, competitive, tech-savvy world they’re growing up in. We’ve heard the stories about kids getting bullied, struggling academically, being exposed to violence at home or school, dealing with economic uncertainty, and worrying about the environment or conflicts in their communities and country. That’s a lot to carry on small shoulders. There’s a lot at stake too. According to Bruce Compas, professor of psychology at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College of Education and Human Development and lead author of a 2017 study published in Psychological Bulletin:

Chronic stress is bad for adults, but it is particularly troublesome for children, because among many other effects, it can disrupt still-developing white matter in the brain, causing long-term problems with complex thinking and memory skills, attention, learning, and behavior.

The effects of stress go deep and lead to problems at school—ones that may go on for years. Parents often don’t realize the lasting effects stress has on kids. In fact, according to a past American Psychological Association (APA) survey, “Stress in America,” parents frequently underestimate what their children are truly feeling. This isn’t due to a lack of concern—more likely it is due to a lack of communication. It isn’t easy to talk about stress, though. Kids may shut down or tune out instead of reaching out. However, we can make it easier to open the lines of communication.

Here are five ways to get kids talking about . . . and coping with stress.

- Point out the physical signs. Did you know that stress in kids often stays hidden because its symptoms are physical? For example, a child may frequently stay home from school or leave the classroom due to headaches or stomachaches—and everyone assumes the child is getting sick. Physical stress symptoms also include difficulty sleeping, restlessness, lack of appetite, or bed-wetting. Let kids in your care know that stress can be a full-body experience:

- aching head

- dry mouth

- heart palpitations

- stomach “butterflies”

- sweating under the arms and of hands and feet

- muscle tension

- that feeling of “I want to crawl out of my skin”

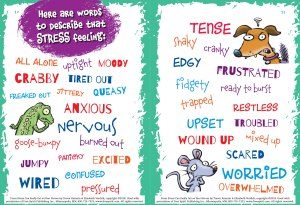

Develop a feelings vocabulary. Younger children may not have a wide vocabulary for describing their emotions—yet. But they’ll get there with your help. Introduce them to words that express a wide variety of stress-related emotions. Encourage them to be specific about how they’re feeling—and then to share that with someone they trust, like a parent or relative. This helps start the conversation that many families need to have.

Develop a feelings vocabulary. Younger children may not have a wide vocabulary for describing their emotions—yet. But they’ll get there with your help. Introduce them to words that express a wide variety of stress-related emotions. Encourage them to be specific about how they’re feeling—and then to share that with someone they trust, like a parent or relative. This helps start the conversation that many families need to have.

- Acknowledge that stress isn’t all bad. Sometimes, a little stress is the jump start we need to complete a task or reach a goal. Knowing that homework is due is a motivator. Feeling pumped up about an upcoming game can help an athlete concentrate and succeed. This type of “normal”—temporary—stress gives someone an edge. You can explain the “fight, flight, or freeze” response that’s built into our systems as a way to protect ourselves from danger or handle risks. Our bodies, whether we’re young or old, respond to stressors through wanting to fight off danger, flee from it, or freeze and hide. When someone feels that urge to fight, run, or hide, he or she can use strategies to calm down and think through what to do. Encourage children under stress to breathe deeply, take a moment to think, talk themselves down, and—if needed—ask for help. Here’s where that feelings vocabulary can come in handy: “I’m mixed up and wound up. Can you help?” “I’m queasy and uneasy. What can I do?”

Talk about schedules. Many kids today live quite structured lives—going from school to organized sports to lessons—with less free time to explore the outdoors or sit back and daydream. Often, a child’s downtime is spent on a screen: playing electronic games, using social media, or watching videos online. This isn’t true for all kids in all families, but people are noticing the changes that tight schedules and technology may bring. You could find out if a child’s anxious feelings are linked to having too much to do or, possibly, to “techno-stress.” Kids who are overloaded may wish to reduce their extracurricular activities for a while to see if spending more time with family and having more free time helps. A crucial tool for families is to have a “media plan” in place so each family member is held accountable for how much time is spent online, in front of the TV, and on a phone or tablet. Keep this plan positive. Families can have fun using screens together! This media plan can be a good start. (And less time with screens means more time with each other—talking.)

Talk about schedules. Many kids today live quite structured lives—going from school to organized sports to lessons—with less free time to explore the outdoors or sit back and daydream. Often, a child’s downtime is spent on a screen: playing electronic games, using social media, or watching videos online. This isn’t true for all kids in all families, but people are noticing the changes that tight schedules and technology may bring. You could find out if a child’s anxious feelings are linked to having too much to do or, possibly, to “techno-stress.” Kids who are overloaded may wish to reduce their extracurricular activities for a while to see if spending more time with family and having more free time helps. A crucial tool for families is to have a “media plan” in place so each family member is held accountable for how much time is spent online, in front of the TV, and on a phone or tablet. Keep this plan positive. Families can have fun using screens together! This media plan can be a good start. (And less time with screens means more time with each other—talking.)

- Help kids connect. Children spend a big part of every day at school, a place where they may feel stressed and disconnected. As a teacher, you can better teach and reach kids if they trust and feel connected to you. Greet them at the door each day—making eye contact, smiling, saying hello, and even building connections through handshakes, high fives, or fist bumps. Show an interest in your students’ cultures, lives, and families. Journal prompts with responses are a good way to get to know kids better—and to let them know more about you. You can also help kids connect with each other through team-building activities and noncompetitive games. Children who feel welcomed and connected and who have a sense of belonging are less stressed. They sense that support will be there when they need it, and this makes them more likely to talk about what’s bothering them and work with you and their parents to find solutions.

Stress may be a pain in the brain, but there’s good news. Bruce Compas puts it this way: “[T]he brain is malleable. Once positive coping skills are learned and put into practice, especially as a family, they can be used to manage stress for a lifetime.” A lifetime. Stress-busting skills learned as a child can be used all the way into adulthood, building stronger families and brighter futures—with a little help from you.

Cited:

Compas, B. E., et al. “Coping, Emotion Regulation, and Psychopathology in Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analysis and Narrative Review.” Psychological Bulletin, 143, no. 9 (Sept. 2017): 939–991.

“5 Stress Management Strategies for Kids” originally appeared at freespiritpublishingblog.com. Copyright © 2020 by Free Spirit Publishing. All rights reserved.