Yes. Yes I do.

Sure, I know there’s a whole school of thought that says “sharing a message” in a children’s book is something to avoid. That children will learn more, feel more, by reading books—stories—that evoke an emotional response and increase empathy through strong characterization and vivid language. Yes. Yes that’s true. But.…

Sometimes children, and the adults raising and teaching them, need straightforward tools that address social and emotional challenges and milestones. Nonfiction books can fit that purpose. Especially if they’re created with certain age groups in mind.

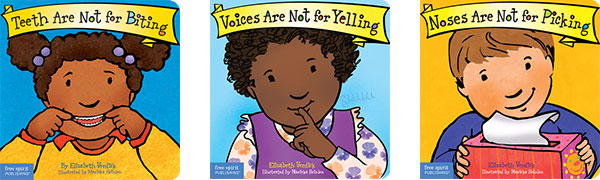

Let’s talk toddlers. This is one of my favorite groups of people — and readers (even though they can’t yet read). Toddlers are energetic, curious, effervescent. They soak up the sights, sounds, and textures of the world — everything’s new. Toddlers have big emotions, ones they often can’t fully understand or explain because they don’t yet have the words. My toddler books aim to give them these words — simple, straightforward phrases that help their days go more smoothly. I have a series of board books called “Best Behavior,” in which the titles are the basis for recurrent phrases in the text: Teeth Are Not for Biting, Words Are Not for Hurting, Germs Are Not for Sharing, Pacifiers Are Not Forever. You can see the message loud and clear — no guessing here!

The simplicity has its purpose — the phrases are a cue. You see a child start to bite a friend, and the phrase “Teeth Are Not for Biting” is a simple reminder. And it’s a more positive use of language than “No biting” or “Don’t bite” or “Stop!” I’m happy that the books steer clear of “Nos” and “Don’ts.” Parents and educators using the series have found that the words in their own homes and classrooms shift in a more positive direction, just as the behavior eventually does. Educators keep sending me topic suggestions, including the recent Voices Are Not for Yelling and Noses Are Not for Picking. (Thank you, teachers, you’re amazing brain-stormers!)

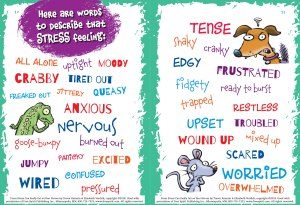

I also write “message” books for older kids, including a series called “Laugh and Learn,” for children ages 8 – 13. In the books, advice and humor go hand in hand. It’s lots of fun titling these books: Dude, That’s Rude, Get Some Manners! or Stress Can Really Get on Your Nerves! Anytime I talk to teachers about this series, I suggest they write a book for it. Who knows kids better than teachers? Educators care so much and see what kids need. When writing nonfiction that has a message, the “way in” can be humor. No one wants a message-heavy or preachy book. But one that’s informative and entertaining — while helping a student grow social/emotional skills — serves an important need. Children may not always want to open up about personal challenges they face. But opening a book that covers the topic? That’s easier.

I’m no special expert. I’m a mom who loves kids, books, and writing. When I write nonfiction that aims to help children understand their emotions or the social world, I think about a voice that can reach and teach without making a child slam the book shut in boredom. I want kids to feel heard. I want them to feel strong. I want them to know they’re not alone. Just like you do. When you stand in front of a classroom or do a presentation in the library, you find creative ways to get kids’ attention and sustain it. You sense their needs and questions. You invite them in.

Want to try your hand at nonfiction that addresses children’s social and emotional needs?

- Know your age group: There are board books for babies and toddlers, illustrated books for PreK and early elementary, books for upper elementary and middle school, and more comprehensive ones for teens. The length and use of language reflects the age of readers.

- Explore educational publishing: Many publishers specifically serve the education market, with books designed mainly for classroom or school library use. Find books you like, and look for the publisher information located on the Library of Congress (LOC) page, which usually appears before the Dedication and Table of Contents. Educational publishers may also list the age/grade, interest, and reading levels there. Once you know the publisher, seek out its guidelines for writing and submission (usually available online).

- Don’t worry about the illustrations: Writers don’t have to become artists — and don’t have to bring in an illustrator. A potential publisher is mainly interested in your words.

- Go to the source: If you’ve got kids of your own or you work in a school, you’re able to observe how children grow, change, and interact. What books might serve their needs? What types of books are their parents looking for?

- Find your voice: Are you funny? Warm and wise? A researcher/fact finder? Do you like to create fun sidebars? Do you enjoy interviewing people? Do you want to use quotes from kids? Do you have an idea for a whole series? There are many “ways in.” Experiment to find what works for you.

Becoming a children’s writer is often a long process of self-discovery, and patience is key (just as in teaching). Your love of kids is a great start. I’m rooting for you!

“You Write Books with … Messages?” originally appeared in Bookology Magazine. Copyright © 2020 by Winding Oak LLC. All rights reserved.

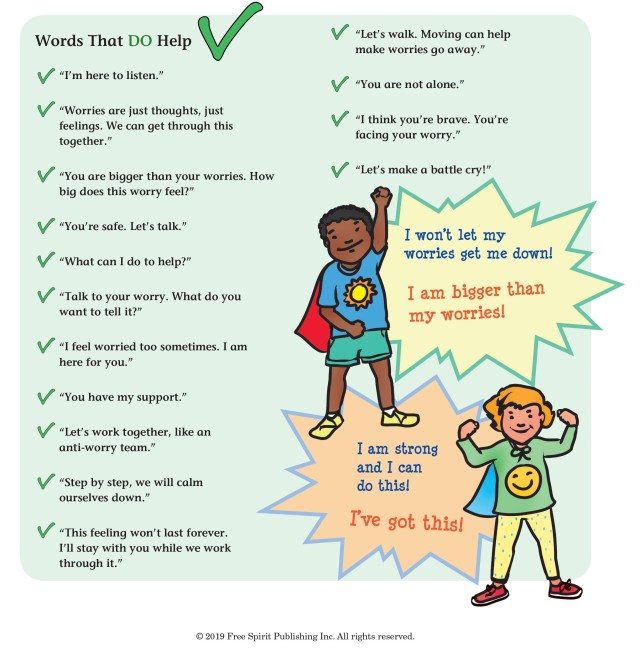

When I tell parents and teachers the title of my new children’s book, Worries Are Not Forever, they often say something like, “I need that immediately” or “Do you have one for adults too?” They laugh a little when they say that, but the underlying meaning is clear: We’re experiencing greater stress in our society, and this stress affects children of all ages—and their families.

When I tell parents and teachers the title of my new children’s book, Worries Are Not Forever, they often say something like, “I need that immediately” or “Do you have one for adults too?” They laugh a little when they say that, but the underlying meaning is clear: We’re experiencing greater stress in our society, and this stress affects children of all ages—and their families.

Elizabeth Verdick has written children’s books for kids of all ages, from toddlers to teens. She has worked on many titles in the Laugh & Learn® series. Elizabeth loves helping kids through her work as a writer and an editor. She lives in Minnesota with her husband and their two (nearly grown) children, and she plays traffic cop for their many furry, four-footed friends

Elizabeth Verdick has written children’s books for kids of all ages, from toddlers to teens. She has worked on many titles in the Laugh & Learn® series. Elizabeth loves helping kids through her work as a writer and an editor. She lives in Minnesota with her husband and their two (nearly grown) children, and she plays traffic cop for their many furry, four-footed friends

A. When I was little, I had a lot of Little Golden Books. Baby’s Mother Goose Pat-a-Cake was one of my early favorites. (I was obsessed with anything that had a cat on it. Still am.) The pages of the book are now faded, yellowed, and torn. The art was by Aurelius Battaglia, and one interior illustration looks a lot like my cat Tom, a tuxedo cat with perfect white mittens and bright green eyes. Now all he needs is a big red bow.

A. When I was little, I had a lot of Little Golden Books. Baby’s Mother Goose Pat-a-Cake was one of my early favorites. (I was obsessed with anything that had a cat on it. Still am.) The pages of the book are now faded, yellowed, and torn. The art was by Aurelius Battaglia, and one interior illustration looks a lot like my cat Tom, a tuxedo cat with perfect white mittens and bright green eyes. Now all he needs is a big red bow.

When you read to your baby, you’re not just bonding, you’re promoting language and social skills. It’s never too early to start a positive lifetime habit.

When you read to your baby, you’re not just bonding, you’re promoting language and social skills. It’s never too early to start a positive lifetime habit.

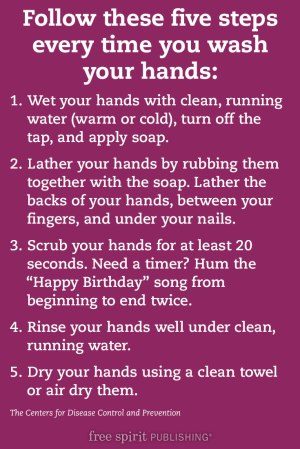

Follow these five steps every time:

Follow these five steps every time:

Storytelling is at the heart of being human—and it starts at birth. We share stories as we talk to our babies, sing to them, and read to them. They grow rich in stories, and once children are verbal, they are eager to share their own tales, eventually writing and drawing them on paper. Storytelling helps children better understand the world, develop empathy, and grow up with greater knowledge and confidence. As an author/illustrator team, we’re grateful that storytelling—via words and art—is our daily work, our way to reach out to readers all over the world. Together, we aim to make books that serve as “mirrors and windows,” helping children build their own social and emotional identities while offering views into other children’s feelings and experiences. We think it’s the best job in the world!

Storytelling is at the heart of being human—and it starts at birth. We share stories as we talk to our babies, sing to them, and read to them. They grow rich in stories, and once children are verbal, they are eager to share their own tales, eventually writing and drawing them on paper. Storytelling helps children better understand the world, develop empathy, and grow up with greater knowledge and confidence. As an author/illustrator team, we’re grateful that storytelling—via words and art—is our daily work, our way to reach out to readers all over the world. Together, we aim to make books that serve as “mirrors and windows,” helping children build their own social and emotional identities while offering views into other children’s feelings and experiences. We think it’s the best job in the world!