When I picture myself as a kid, I think of my bedroom in our split-level West Virginia house, a room I loved but had to leave behind at age eleven when my family moved to Maryland. For years, that room was my own little world, my book nook, my place to cuddle my cat Rag, collect china-cat figurines, and, yes, read books about cats. Was I feline-obsessed? Yes! But I won’t bore you with the list of cat-oriented fiction and nonfiction I consumed as a child. You might be a dog lover after all. My reading taste also included some of the novels that plenty of girls growing up in the seventies loved: the Nancy Drew mysteries, Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, and Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. I also adored books about pigs, and for years, I imagined that someday on one of my family’s many visits to farms and petting zoos, a real-life pig would finally talk to me, confirming my belief that pigs are not only smart but also magical, and good conversationalists, too. That little bedroom was a riot of color: avocado-green shag carpeting, a bright patchwork quilt, yellow furniture, stuffed animals in all shades and states of dress (overalls, tiny skirts, funny hats). It was the place where I could most be myself.

Experts say that around the time of puberty, most girls experience a nosedive in confidence — a crisis that parents and educators have for years tried to address. At age eleven, I couldn’t have put into words how or why my once-fiery self was diminishing week by week, and for years later. The transition from child into teen is intense and often painful, a time when you still believe in talking animals and portals to other worlds yet must face the ways in which your body and self-image are changing day by day. I read and reread books that seemed to hold the answers — or a sense of “I see you.” Like me, Margaret Murry (in A Wrinkle in Time) wrestled with her frizzy hair and teasing peers. Like me, another Margaret (this time in a Judy Blume book) was worried about her family’s move, not to mention bras, boys, and B.O. And there was Harriet, the young “spy” who exuberantly confessed her feelings in her notebook: “I FEEL THERE’S A FUNNY LITTLE HOLE IN ME THAT WASN’T THERE BEFORE, LIKE A SPLINTER IN YOUR FINGER, BUT THIS IS SOMEWHERE ABOVE MY STOMACH” (Harriet the Spy, p.132). I knew that empty feeling. Reading helped fill it.

These protagonists were lifelines when I wanted to hide or cry, laugh and scream at the same time, or just play pretend like a little kid. When you’re not quite a child anymore but you’re not officially a teen, you still feel that urge to become a character you’re reading about: I bought a composition notebook like Harriet’s and spied beneath the neighbors’ windows; I wore borrowed eyeglasses to create my Margaret Murry persona; and I decided to start praying (“Are you there God? It’s me, Elizabeth”). Sometimes I’d pretend to be Nancy Drew, brave and wise beyond her years. Other times I was Fern from Charlotte’s Web, wheeling dolls and my obliging cat in a baby carriage, calling him “Wilbur.” That in-between stage is lonely and confusing, watching your peers play Spin the Bottle when you’d rather be home playing Barbie ER (it involved crashing her Country Camper). Books don’t judge you — they understand. They offer up heroes and add color and magic to everyday life.

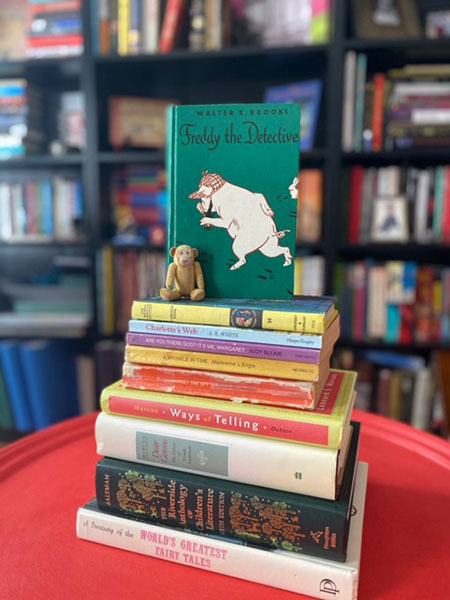

I often felt different from people my age, in that I held on to childhood for so long. Throughout high school, I returned to picture books and my timeworn Judy Blume novels, even though I was also reading Stephen King. I’d pull out my Nancy Drew books, lining them up to choose the best cover or make my room resemble a library. When feeling especially nostalgic, I’d dig out Freddy the Detective, a 1932 novel by Walter R. Brooks about an adventurous, can-do pig, and ask my dad to read aloud. I wanted to publish stories myself someday, but when I later submitted work to my college’s literary magazine, I was told the pieces skewed “too young” and would only appeal to kids.

What I didn’t know then was that there was a whole world of people who loved work that centered on children and teens. When I moved to St. Paul after college, I got a job as a bookseller at the Red Balloon Bookshop, where walking in the front door felt like coming home. Walls of kids’ books! Rows of stuffed-animal literary characters! A visit from the Madeleine L’Engle! There, I didn’t have to be more “adult” than I wanted to be. Maybe those past days of poring over book covers in my bedroom had done more than simply satisfy my curiosity or create a sense of calm. I’d been developing a respect for storytellers and illustrators — perhaps even gaining that first little bit of what Ira Glass of This American Life describes as “taste,” or your impulse to do creative work. I eventually found a job in book publishing, where I learned to edit manuscripts and help design book interiors. I took a class at the University of Minnesota taught by Karen Nelson Hoyle, who had students read The Riverside Anthology of Children’s Literature, which examines the importance of folktales, poetry, picture books, and novels written for young people. I was still a beginner, and as Glass explains (wishing someone had told him when he was a beginner): “All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not … A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit.” I often gave up, shredding my own stories before anyone could see them. But during that time, I helped other writers find their voices and bring their books into the world, a role I cherished.

Something changed, deepened, when I had kids of my own. That call to children’s literature grew even stronger. I took writing classes at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis, and I eventually got an MFA in writing for children and teens from Hamline University in St. Paul. Along the way, I learned from authors whose books elicited the feelings of yearning I’d had at age eleven — Minnesota writers like Anne Ursu and Kate DiCamillo. I studied new and classic picture books, and I longed to write in that short (yet deceptively complex) form. I hoped to someday feel as confident as Harriet M. Welsch, intrepid girl spy and journal-keeper, who used writing to understand the world and herself. That was pie-in-the-sky thinking. Today, any time I start a new manuscript, my confidence plummets and I feel like a beginner again. But guess what? Most writers do! Ira Glass says, “It’s normal to take awhile. You’ve just gotta fight your way through.”

When you read a word-perfect picture book or a beautifully written novel, it’s easy to think the book popped into the world like “Presto!” because you feel the magic as you turn the pages. But writers, illustrators, and editors know how much behind-the-scenes work it takes to create that illusion. If you’re curious about “book-magic,” you might want to read Ways of Telling: Conversations on the Art of the Picture Book by Leonard S. Marcus, and one of Marcus’s other works, Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom, who was the director of Harper’s Department of Books for Boys and Girls from 1940 to 1973 (and editor of classics such as Charlotte’s Web, Goodnight Moon, and Where the Wild Things Are). It’s fascinating to learn about Nordstrom’s correspondence with E. B. White and illustrator Garth Williams, who worked together on Charlotte’s Web. (Should Williams draw Charlotte’s eight eyes? Should her mouth be visible?) In Ways of Telling, author/illustrator Eric Carle reveals that he had created a manuscript called “A Week with Willi Worm!” that, after advice from his editor, transformed into The Very Hungry Caterpillar. Books, like butterflies, emerge only after a messy process of metamorphosis. And that’s fitting because, after all, we’re talking about works for children, who in the words of E. B. White, “… are the most attentive, curious, eager, observant, sensitive, quick, and generally congenial readers on earth.” It’s an honor to write for them.

I’m far from eleven, but I’m still obsessed with cats (dogs too). I’m still waiting for the day a pig might talk to me. And books are still my best friends. Some things never change.

“Self on the Shelf with Elizabeth Verdick” originally appeared in Bookology Magazine. Copyright © 2020 by Winding Oak LLC. All rights reserved.